More than anyone else, John von Neumann created the future. He was an unparalleled genius, one of the greatest mathematicians of the twentieth century, and he helped invent the world as we now know it. He came up with a blueprint of the modern computer and sparked the beginnings of artificial intelligence. He worked on the atom bomb and led the team that produced the first computerized weather forecast. In the mid-1950s, he proposed the idea that the Earth was warming as a consequence of humans burning coal and oil, and warned that “extensive human intervention” could wreak havoc with the world’s climate. Colleagues who knew both von Neumann and his colleague Albert Einstein said that von Neumann had by far the sharper mind, and yet it’s astonishing, and sad, how few people have heard of him.

Just like Einstein, von Neumann was a child prodigy. Einstein taught himself algebra at twelve, but when he was just six von Neumann could multiply two eight-digit numbers in his head and converse in Ancient Greek. He devoured a forty-five-volume history of the world and was able to recite whole chapters verbatim decades later. “What are you calculating?” he once asked his mother when he noticed her staring blankly into space. By eight he was familiar with calculus, and his oldest friend, Eugene Wigner, recalls the eleven-year-old Johnny tutoring him on the finer points of set theory during Sunday walks. Wigner, who later won a share of the Nobel prize in physics, maintained that von Neumann taught him more about math than anyone else.

Johnny’s plans (and by extension, the modern world) were nearly derailed by his father, Max, a doctor of law turned investment banker. “Mathematics,” he maintained, “does not make money.” The chemical industry was in its heyday so a compromise was reached that would mark the beginning of von Neumann’s peripatetic lifestyle: the boy would bone up on chemistry at the University of Berlin and meanwhile would also pursue a doctorate in mathematics at the University of Budapest.

In the event, mathematics did make von Neumann money. Quite a lot of it. At the height of his powers in the early 1950s, when his opinions were being sought by practically everyone, he was earning an annual salary of $10,000 (close to $200,000 today) from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, the same again from IBM, and he was also consulting for the US Army, Navy and Air Force.

Von Neumann was irresistibly drawn to applying his mathematical genius to more practical domains. After wrapping up his doctoral degree, von Neumann moved to Göttingen, then a mathematical Mecca. There was also another boy wonder, Werner Heisenberg, who was busily laying the groundwork of a bewildering new science of the atom called “quantum mechanics.” Von Neumann soon got involved, and even today, some of the arguments over the limits and possibilities of quantum theory are rooted in his clear-eyed analysis.

Sensing early that another world war was coming, von Neumann threw himself into military research in America. His speciality was the sophisticated mathematics of maximizing the destructive power of bombs — literally how to get the biggest bang for the army’s buck. Sent on a secret mission to England in 1943 to help the Royal Navy work out German mine-laying patterns in the Atlantic, he returned to the US when the physicist Robert Oppenheimer begged him to join America’s atom-bomb project. “We are,” he wrote, “in what can only be described as a desperate need of your help.”

Terrified by the prospect of another world war, this time with Stalin’s Soviet Union, von Neumann would help deliver America’s hydrogen bomb and smooth the path to the intercontinental ballistic missile.

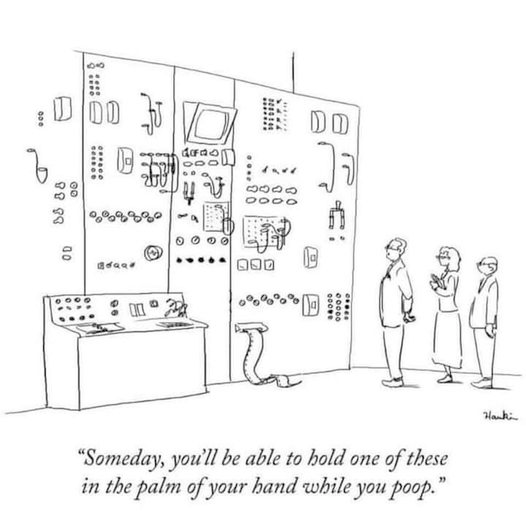

As he scoured the US for computational resources to simulate bombs, he came across the ENIAC, a room-filling machine at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania that would soon become the world’s first fully electronic digital computer. The ENIAC’s sole purpose was to calculate trajectories for artillery. Von Neumann, who understood the true potential of computers as early as anyone, wanted to build a more flexible machine, and described one in 1945’s First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC. Nearly every computer built to this day, from mainframe to smartphone, is based on his design. When IBM unveiled their first commercial computer, the 701, eight years later, it was a carbon copy of the one built earlier by von Neumann’s team at the IAS.

While von Neumann was criss-crossing the States for the government and military, he was also working on a 1,200-page tract on the mathematics of conflict, deception and compromise with the German economist Oskar Morgenstern. What was a hobby for von Neumann was for Morgenstern a “period of the most intensive work I’ve ever known.” Theory of Games and Economic Behavior appeared in 1944, and it soon found favor at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, where defense analysts charged with “thinking about the unthinkable” would help shape American nuclear policy during the Cold War. They persuaded von Neumann to join RAND as a consultant, and their new computer was named the Johnniac in his honor.

Since then, game theory has transformed vast tracts of economics, the wider social sciences and even biology, where it has been applied to understanding everything from predator-prey relationships to the evolution of altruistic behavior. Today, game theory crops up in every corner of internet commerce — but most particularly in online advertising, where ad auctions designed by game theorists net the likes of Google and Amazon billions of dollars every year.

More at this link